Research

Development of the Concept of Age

Age is a very salient and important concept in our social world, yet little is known about how children come to understand it. In a first project, with

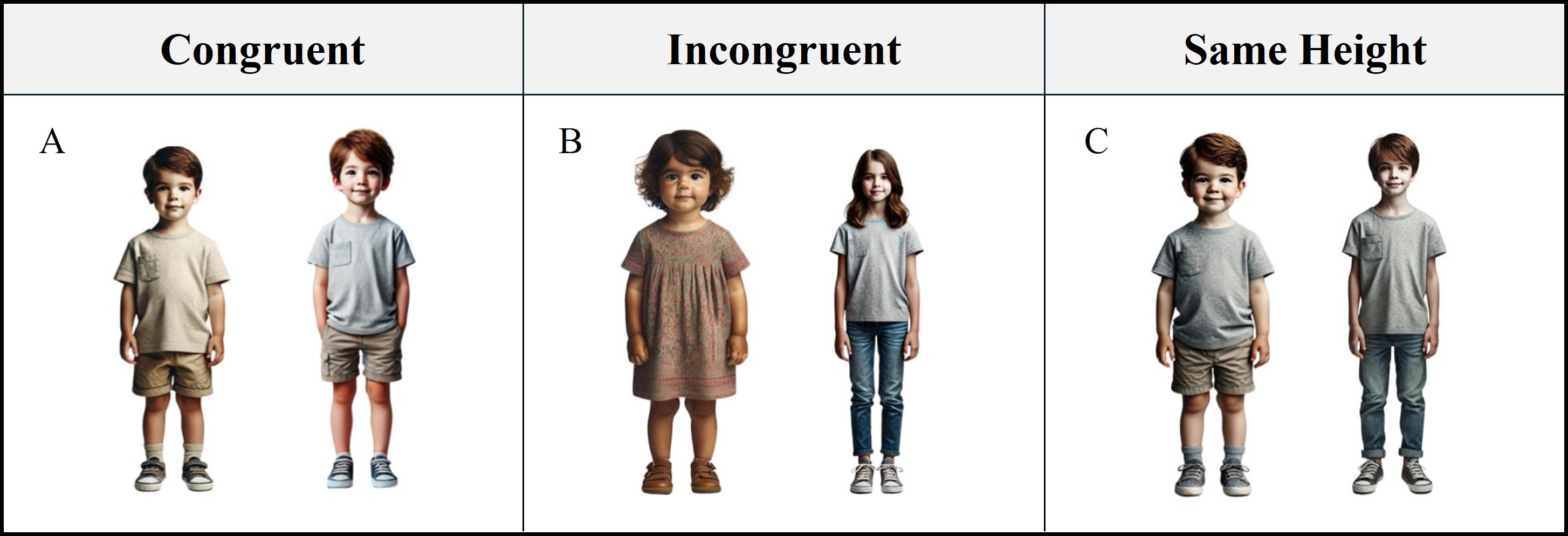

David Barner, we found that preschool-aged children are able to use cues such as numerical age and facial and bodily morphology to judge which of two people is older, even if the older person was made to look smaller. Furthermore, we found that children's age judgments were related to their numerical knowledge. This suggests that children may not initially conflate age with size as suggested by prior studies, and that children only base age judgments on size when other cues are unavailable or not sufficiently discriminable.

Read More

In a current project, we are asking whether children's understanding of age group labels such as "grown up" and "child" at 3 years old reflects young children's understanding of the chronological progression of aging, or if children have only formed categories of people and mapped them onto these labels without understanding age chronologically yet. If the latter is true, it would suggest that these early-formed categories of age groups may serve as placeholder structures in a boostrapping process of understanding age, with the development of the ability to think about time chronologically and quantitatively, potentially aided by the acquisition of a number system, later enabling these categories to be transferred onto a chronological representation of age. Finally, another project investigates whether 4- to 6-year-old children are able to use age to guide a range of inferences about people, such as their cognitive and physical development, their authority or dependency, and their preferences.

Development of Temporal Quantification

Words which denote temporal durations are highly prevalent in natural language but appear to pose a learning challenge for young children. With

David Barner, we investigate the challenges children may face in learning time words through a case study of the comparative "more". We ask whether 3- to 4-year-old children are able to comprehend "more" as applied to temporal duration (e.g., "John danced more than Mary"). On the one hand, that children only learn the precise meanings of words which denote temporal durations (e.g., "second", "hour") at 6 or 7 years old might suggest that young children may face a similar delay in learning "more" in reference to duration. On the other hand, prior research which has demonstrated comprehension of "more" in reference to numerical and spatial quantities at 3 years old and theories which posit a domain-general magnitude system common to number, space, and time may suggest that children would be able to apply their understanding of "more" to time already at 3 years old. Through this investigation, we aim to shed light on the mechanisms of time word learning and the relation of temporal quantification to quantification in other domains.

Learning Abstract Nouns from Visual Scenes

Although the child's first few words label whole, concrete objects (e.g., "ball"), such highly concrete words make up only a small fraction of the adult lexicon. How, then are more abstract words learned? With

Umay Suanda, we investigate the informativity of visual scenes for learning hard nouns, a class of abstract words. We reinvestigate the claim that the meanings of hard nouns cannot be learned from the visual scenes they co-occur with. Rather, through an adult cross-situational word learning task which includes several novel tests of learning, we find that although it is indeed difficult to learn the full meaning of a hard noun from its observational contexts, these visual scenes may inform a significant amount of systematic partial knowledge of the word's meaning. It is possible that this foundation of knowledge about the word's meaning plays a role in leading the learner to full understanding when other sources of information, such as linguistic contexts, are incorporated.

Age is a very salient and important concept in our social world, yet little is known about how children come to understand it. In a first project, with David Barner, we found that preschool-aged children are able to use cues such as numerical age and facial and bodily morphology to judge which of two people is older, even if the older person was made to look smaller. Furthermore, we found that children's age judgments were related to their numerical knowledge. This suggests that children may not initially conflate age with size as suggested by prior studies, and that children only base age judgments on size when other cues are unavailable or not sufficiently discriminable. Read More